A grounded map for the inner transformation process

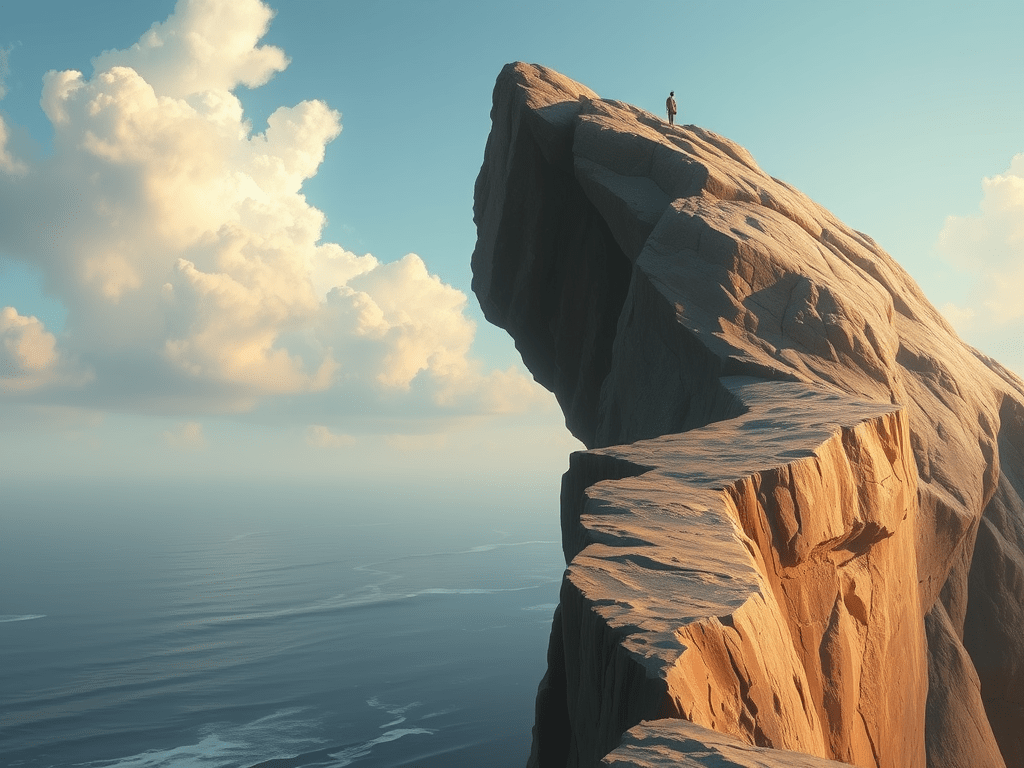

There is a version of awakening that sounds dramatic, luminous, and otherworldly.

And then there is the version most people actually live through.

It doesn’t begin with angels or light shows.

It begins with disruption.

Something no longer fits.

Old motivations feel hollow.

Reactions feel bigger than the moment.

The life that once made sense starts to feel strangely distant.

This is often where fear enters. Because without context, awakening doesn’t feel like expansion.

It feels like losing your footing.

This piece offers a grounded, human map — not to define your experience, but to help you recognize that what feels like chaos is often a deeply intelligent reorganization.

Stage 1 — Disruption: When the Old Framework Cracks

Awakening often begins with a rupture in the story you’ve been living inside.

It might come through:

- burnout

- heartbreak

- illness

- sudden success that feels empty

- a quiet but persistent sense that “this isn’t it”

Things that once motivated you lose their charge.

Roles you played comfortably start to feel like costumes.

This is not failure.

It is the first sign that your inner system has outgrown its previous structure.

But because the new structure hasn’t formed yet, this phase feels like groundlessness.

Stage 2 — Identity Loosening: Who Am I Without the Old Script?

As the old framework weakens, identity begins to soften.

You may notice:

- less certainty about who you are

- discomfort in social roles that used to feel natural

- grief over versions of yourself that are fading

- a strange mix of relief and loss

This can feel like regression, but it is actually deconstruction.

Your nervous system is learning that it is safe to exist without constantly performing a familiar identity. That takes time, and it often comes with emotional swings.

Stage 3 — Emotional Waves: Highs, Lows, and Everything Between

Many people expect awakening to feel peaceful. Instead, it often feels like an emotional tide.

Moments of clarity and connection may be followed by:

- sadness with no clear story

- irritation that feels out of proportion

- exhaustion

- unexpected grief

This happens because emotional material that was previously held in place by your old identity is now free to move.

Nothing is wrong.

Your system is clearing space.

These waves are not signs that you are failing. They are signs that your inner life is reorganizing at a deeper level than before.

Stage 4 — Meaning Collapse: When Certainty Falls Away

At some point, the mind tries to regain control by demanding answers.

What is happening to me?

What do I believe now?

Where is this going?

But awakening often includes a phase where previous belief systems — spiritual, personal, or practical — no longer feel solid.

This can feel like emptiness. Like standing in fog.

It is tempting to grab onto the next explanation that offers certainty.

But this quiet, uncertain space is not a void to escape. It is a reset field where deeper alignment can emerge without being forced.

Stage 5 — Quiet Integration: The Lull That Feels Like Nothing

After intense emotional or perceptual shifts, many people experience a phase that feels surprisingly flat.

Life looks ordinary again.

Routines return.

There are fewer dramatic insights.

This is not the end of awakening. It is where the change starts to root.

Your nervous system is learning to hold a new baseline. The absence of intensity can feel like regression, but it is actually stabilization.

This is where the work becomes less visible — and more real.

Stage 6 — Embodiment Practices: Letting the Body Catch Up

As awareness expands, the body needs support to integrate.

This often looks very simple:

- regular sleep

- mindful breathing

- time in nature

- journaling

- gentle movement

- reducing overstimulation

These are not “beginner practices.” They are how expanded awareness becomes livable.

Awakening that stays in the mind creates imbalance. Awakening that moves into the body creates coherence.

Stage 7 — Stabilized Presence: Less Drama, More Depth

Over time, something subtle but profound shifts.

You may notice:

- fewer extreme reactions

- more space between trigger and response

- less urgency to prove or explain yourself

- a growing comfort with not knowing everything

This is not indifference. It is regulation.

You are no longer riding every emotional wave as if it defines reality. You can feel deeply without being swept away.

This is where awakening becomes less of an experience and more of a way of being.

Stage 8 — Passive Influence: How Change Spreads Without Force

At this point, many people feel the urge to “share what they’ve learned.”

But the most powerful form of sharing now looks different.

You are steadier in conflict.

You listen without immediately fixing.

You respond with more patience than before.

Others feel this, even if they can’t name it.

Change begins to ripple not through explanation, but through the emotional climate you help create. This is how transformation spreads naturally — one regulated human influencing another through presence, not persuasion.

The Bigger Picture

Stripped of mystical language, awakening is not an escape from being human.

It is a deepening into it.

It is your system learning to operate with more honesty, more regulation, and more alignment between inner truth and outer life.

There will be beauty.

There will be discomfort.

There will be periods that feel like falling apart.

But much of what feels like collapse is actually construction happening out of sight.

You are not breaking.

You are reorganizing.

And like any profound reorganization, it happens in phases — some bright, some quiet, all meaningful.

Light Crosslinks

You may also resonate with:

• The Quiet Integration Phase After Awakening

• Why You Can’t Wake Someone Up Before They’re Ready

• Living Change Without Explaining Yourself

About the author

Gerry explores themes of change, emotional awareness, and inner coherence through reflective writing. His work is shaped by lived experience during times of transition and is offered as an invitation to pause, notice, and reflect.

If you’re curious about the broader personal and spiritual context behind these reflections, you can read a longer note here.