Tracing how early coping strategies become adult identities — and where the cycle can change

Prologue — Adaptation Is Not Destiny

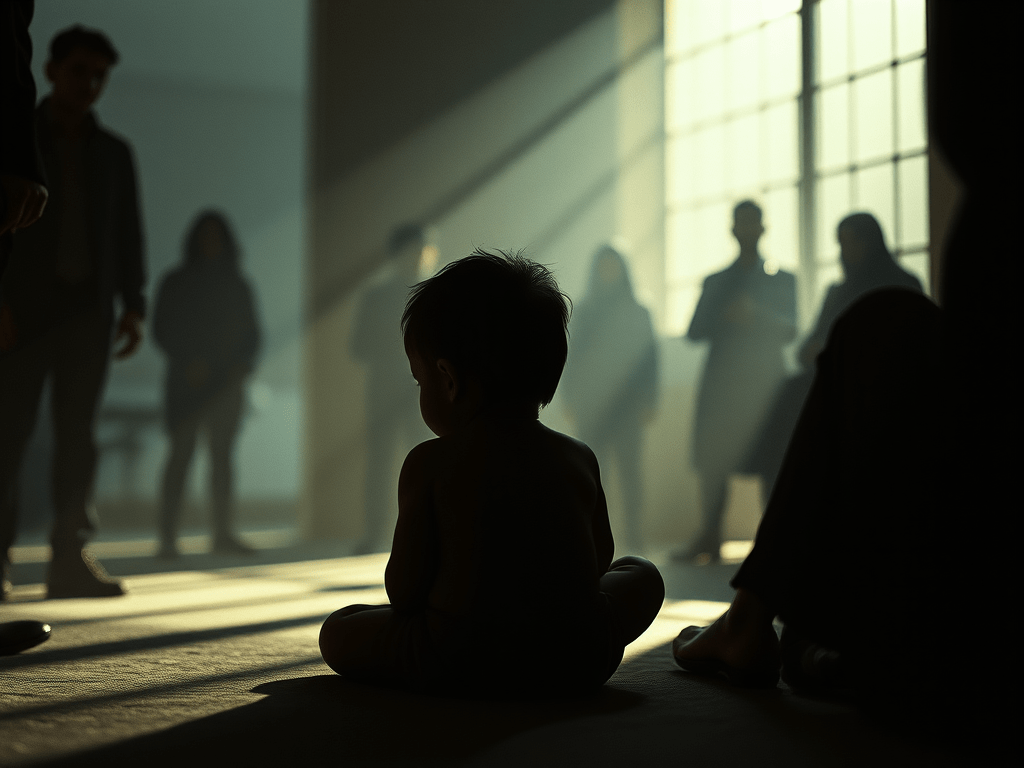

Before memory, there was adaptation.

Before identity, there was response.

Each soul enters a world already in motion — shaped by family histories, emotional climates, and unspoken survival rules. The young nervous system does not analyze; it learns. It reads tone, absence, intensity, and safety, shaping itself to endure what it cannot yet change.

A child raised in safety learns trust.

A child raised in unpredictability learns vigilance.

A child raised in neglect learns self-reliance.

A child raised in control learns compliance — or resistance.

These early adjustments are acts of intelligence. They preserve connection. They protect life. They arise automatically, guided by the body’s instinct to survive within the conditions it is given.

The difficulty begins when temporary survival strategies become permanent personality structures — when what once ensured endurance continues long after the original environment has changed.

What once protected begins to define.

This Codex is not a judgment of the past. It is an illumination of the hinge point where inheritance becomes choice. Here we look gently at the survival strategies that formed us — not to reject them, but to recognize where they are no longer required.

For in the moment awareness dawns, repetition loosens.

And what once moved through us automatically becomes something we can reshape with care.

I · Survival Strategies That Outlive Their Environment

In childhood, the nervous system organizes around one question:

“What must I do to stay safe here?”

The answers become patterns:

| Early Environment | Survival Adaptation | Adult Echo |

|---|---|---|

| Emotional unpredictability | Hypervigilance | Anxiety, control-seeking |

| Neglect | Self-sufficiency | Difficulty receiving support |

| Harsh authority | Compliance or rebellion | People-pleasing or oppositional behavior |

| Power abuse | Identification with power | Controlling leadership styles |

These responses are not moral failings. They are intelligent adjustments to early reality. However, when circumstances change but the adaptation remains, a mismatch develops between present reality and past conditioning.

II · The Repetition Effect — Familiar Feels Like “Normal”

Humans tend to recreate familiar emotional environments, even when those environments were painful.

This is not because people consciously desire suffering. It is because the nervous system equates familiarity with predictability, and predictability with safety.

This dynamic has been studied in trauma psychology by figures like Bessel van der Kolk, who describes how the body retains implicit memories of early stress and continues to react as if old conditions are still present.

Examples of repetition patterns include:

- Abused children becoming abusive parents

- Children of emotionally distant caregivers becoming emotionally unavailable partners

- Individuals raised in scarcity becoming hoarders when resources become available

- Employees harmed by authoritarian leaders later adopting the same leadership style

The original wound is not being reenacted intentionally.

It is being replayed automatically.

III · Identification With the Aggressor

One powerful survival mechanism is identification with the source of power.

When someone feels powerless in early life, they may unconsciously conclude:

“Power is what prevents harm.”

Later, when they gain authority, the nervous system may default to the same behaviors once feared. This dynamic has been observed in both personal and political contexts, including the rise of authoritarian personalities like Adolf Hitler and Joseph Stalin, whose regimes reflected cycles of fear, control, and domination that often mirror unresolved trauma at scale.

At a smaller scale, this same mechanism appears in:

- Abusive supervisors

- Controlling parents

- Intimidating partners

The individual is not becoming “evil.”

They are repeating a survival equation learned early:

Power = Safety

IV · From Personal Pattern to Social Structure

When large numbers of individuals carry unexamined survival adaptations into adulthood, these patterns shape institutions.

Scarcity-minded individuals build competitive systems.

Control-oriented individuals create rigid hierarchies.

Emotionally disconnected individuals design impersonal structures.

Over time, society reflects the accumulated survival strategies of its members.

This is how childhood wounds scale into:

- Authoritarian governance

- Workplace cultures built on fear

- Economic systems rooted in hoarding and competition

The system is not separate from people.

It is a mirror of unprocessed conditioning.

V · The Turning Point — Consciousness Creates Choice

The cycle begins to loosen at a precise moment:

When a person recognizes, “This reaction belongs to my past, not my present.”

This awareness creates a gap between impulse and action.

Instead of automatically repeating the pattern, a new question becomes possible:

“Given who I am now, what do I choose instead?”

This is not denial of the past.

It is the reclamation of authorship over the future.

Neuroscience research on neuroplasticity, advanced by scientists like Norman Doidge, shows that repeated conscious choices can reshape neural pathways over time. Patterns are learned — and can be relearned.

VI · Changing the Cycle One Person at a Time

Systemic change often feels overwhelming. But generational cycles do not break at the level of systems first. They break at the level of individuals who choose not to pass forward what they inherited.

Each time someone:

- Pauses instead of reacting

- Listens instead of dominating

- Shares instead of hoarding

- Repairs instead of withdrawing

…a survival adaptation is being updated.

The shift may seem small, but patterns propagate socially. Children raised by even slightly more regulated caregivers develop different nervous system baselines. Employees led by self-aware managers create different workplace norms.

One regulated person influences many others.

Closing Reflection — The Future Is Not Obligated to the Past

Early life shapes us, but it does not imprison us.

Adaptations formed under pressure were necessary then. They deserve understanding, not shame. Yet what once ensured survival does not have to dictate the future.

Conscious awareness is the leverage point where history loosens its grip.

From there, the cycle shifts:

Not by force.

Not by denial.

But by repeated, present-moment choice.

When one person interrupts a pattern, the future quietly changes direction.

Related Readings

If this exploration of inherited survival patterns resonated, these pieces expand the lens from personal conditioning to relational and systemic flow:

🔹 From Learned Helplessness to Personal Agency

Looks at how long-term powerlessness can become an identity — and how agency can be rebuilt gently, one conscious choice at a time.

🔹 Repair Before Withdrawal

Explores the instinct to pull away when old wounds are activated, and why small acts of repair can interrupt repeating relational cycles.

🔹 Four Horsemen of Relationships — Early Warning & Repair

Examines how protective behaviors formed in stress can quietly erode connection — and how awareness restores emotional circulation.

🔹 From Survival to Scarcity — How an Adaptive Instinct Became a Global System

Traces how personal survival fear scaled into economic and social structures, showing how unconscious patterns shape collective reality.

🔹 The Ethics of Receiving

A reflection on how difficulty receiving often traces back to early survival conditioning, and how balanced exchange supports healing and trust.

About the author

Gerry explores themes of change, emotional awareness, and inner coherence through reflective writing. His work is shaped by lived experience during times of transition and is offered as an invitation to pause, notice, and reflect.

If you’re curious about the broader personal and spiritual context behind these reflections, you can read a longer note here.