Category: Philippines

-

Strong Women of the Philippines: Pioneers of Gender Equality in Asia

Harnessing Women’s Empowerment for National Development and Global Inspiration

Prepared by: Gerald A. Daquila, PhD. Candidate

8–11 minutesABSTRACT

The Philippines stands out in Asia as a leader in gender equality, with women wielding significant influence in business, government, and family life. This dissertation explores the historical, cultural, and socioeconomic factors behind this phenomenon, using a multidisciplinary lens that includes historical, sociological, feminist, and economic perspectives. It traces the roots of women’s empowerment to pre-colonial egalitarianism, colonial reforms, and modern legislation like the Magna Carta of Women.

The study highlights lessons for other nations, such as robust legal frameworks, education access, and cultural openness to women’s leadership, while assessing societal gains in economic growth, governance, and family resilience. It also examines challenges posed by Overseas Filipino Workers (OFWs) and the potential legalization of divorce. By emphasizing how the Philippines can leverage its gender equality model for national development and global influence, this work offers a compelling, accessible narrative for a wide audience, balancing scholarly rigor with emotional resonance.

Table of Contents

- Introduction

- The Philippines as a Gender Equality Leader

- Purpose and Scope of the Study

- Historical Foundations of Women’s Empowerment

- Pre-Colonial Gender Roles

- Colonial Influences and Suffrage Movements

- Post-Independence Progress

- Women in Business, Government, and Family

- Business: Breaking the Glass Ceiling

- Government: Trailblazing Female Leadership

- Family: Matriarchal Influence and Egalitarian Dynamics

- Feminist Perspectives on Filipino Women’s Empowerment

- Liberal and Post-Colonial Feminism

- Challenges of Patriarchy and Cultural Norms

- Lessons for Other Countries

- Legal Frameworks and Policy Advocacy

- Education and Economic Opportunities

- Cultural Shifts Toward Gender Inclusivity

- Societal Gains from Strong Women’s Representation

- Economic Contributions

- Inclusive Governance

- Social Cohesion and Family Resilience

- Challenges and Future Impacts

- The Role of Overseas Filipino Workers (OFWs)

- The Potential Legalization of Divorce

- Conclusion

- Synthesis of Findings

- Leveraging Women’s Empowerment for Development and Progress

- Glossary

- Bibliography

Glyph of the Bridgewalker

The One Who Holds Both Shores.

1. Introduction

The Philippines as a Gender Equality Leader

In a region often bound by patriarchal norms, the Philippines shines as a beacon of gender equality, ranking 17th globally in the 2021 Global Gender Gap Index, closing 78.4% of its gender gap (World Economic Forum, 2021). Filipino women hold prominent roles in business, government, and family, often surpassing men in influence. From Corazon Aquino’s historic presidency to women leading major corporations, this phenomenon sets the Philippines apart in Asia. This dissertation explores the roots of this empowerment, its societal impacts, and how it can drive national development and global inspiration.

Purpose and Scope of the Study

This study examines the origins of Filipino women’s empowerment through historical, sociological, feminist, and economic lenses. It addresses: How did this unique model emerge? What can other nations learn? How have societal gains manifested, and what challenges lie ahead? With a focus on leveraging women’s strengths for progress, it blends academic rigor with accessible storytelling to engage a broad audience.

2. Historical Foundations of Women’s Empowerment

Pre-Colonial Gender Roles

Before Spanish colonization, Filipino society embraced egalitarian gender norms. The babaylan, often women, served as spiritual and community leaders alongside male datus (Salazar, 2003). Women engaged in trade and controlled household finances, laying a foundation for matriarchal influence.

Colonial Influences and Suffrage Movements

Spanish colonization (1565–1898) introduced Catholicism, reinforcing patriarchal family structures, yet women retained domestic authority. The American period (1898–1946) brought educational reforms, enabling women’s access to schools. The suffrage movement, inspired by Western suffragettes like Carrie Chapman Catt, led to the 1937 plebiscite, making the Philippines the first Asian nation to grant women voting rights.

Post-Independence Progress

Post-World War II, women rose in politics and business. The 1986 People Power Revolution, led by Corazon Aquino, marked a turning point, with her presidency (1986–1992) symbolizing women’s political power. The Magna Carta of Women (2009) further solidified protections against discrimination.

3. Women in Business, Government, and Family

Business: Breaking the Glass Ceiling

Filipino women hold 69% of senior management roles, the highest in Southeast Asia (Grant Thornton, 2020). Leaders like Teresita Sy-Coson of SM Investments exemplify this trend. Education access and supportive policies drive success, though low female labor force participation (49% in 2019) remains a challenge.

Government: Trailblazing Female Leadership

The Philippines has elected two female presidents—Corazon Aquino and Gloria Macapagal-Arroyo—and influential senators like Miriam Defensor-Santiago. The party-list system, including groups like Gabriela, amplifies women’s legislative voices. The 5% Gender and Development (GAD) budget prioritizes women’s issues.

Family: Matriarchal Influence and Egalitarian Dynamics

Filipino women often control household budgets and decisions, rooted in pre-colonial practices. Even in transnational OFW families, mothers maintain central roles, fostering resilience and adaptability.

4. Feminist Perspectives on Filipino Women’s Empowerment

Liberal and Post-Colonial Feminism

Liberal feminism, evident in suffrage and the Magna Carta, emphasizes legal equality. Post-colonial feminism highlights how colonial legacies and global migration shape Filipina experiences, particularly for OFWs facing deskilling abroad.

Challenges of Patriarchy and Cultural Norms

Catholicism and traditional norms limit women’s autonomy, with divorce and abortion remaining illegal. Sexist rhetoric, like that of former President Rodrigo Duterte, persists, but movements like #BabaeAko demonstrate women’s resistance.

Glyph of Filipina Strength

Honoring the strong women of the Philippines — pioneers of gender equality and leadership in Asia.

5. Lessons for Other Countries

Legal Frameworks and Policy Advocacy

The Magna Carta of Women provides a model for comprehensive gender legislation, addressing workplace rights, violence, and education. Other nations can adopt similar policies to institutionalize equality.

Education and Economic Opportunities

High female literacy (90.4% vs. 80.6% for males) fuels women’s success. Investing in education and flexible work arrangements can boost female labor participation globally.

Cultural Shifts Toward Gender Inclusivity

The Philippines’ cultural acceptance of women’s leadership, rooted in pre-colonial egalitarianism, suggests that challenging traditional gender roles can foster equality. Advocacy campaigns can drive similar shifts worldwide.

6. Societal Gains from Strong Women’s Representation

Economic Contributions

Women’s leadership in business drives innovation and growth. Female OFWs, comprising 60.2% of overseas workers in 2021, contribute 9.6% to GDP through remittances, reducing poverty and enhancing family welfare.

Inclusive Governance

Female leaders prioritize social welfare and education, fostering inclusive policies. The GAD budget ensures gender considerations in governance, promoting equity.

Social Cohesion and Family Resilience

Women’s central role in families strengthens social bonds. In OFW households, women’s remittances and decision-making sustain family units, despite emotional challenges.

7. Challenges and Future Impacts

The Role of Overseas Filipino Workers (OFWs)

In 2021, 60.2% of OFWs were women, often in feminized roles like nursing. While remittances empower families, migration leads to deskilling, mental health issues, and family strain. Wives of OFWs show resilience through community support.

The Potential Legalization of Divorce

Divorce remains illegal due to Catholic influence, but debates, supported by figures like Miriam Defensor-Santiago, suggest change. Legalization could empower women to escape abusive relationships but may face conservative resistance.

8. Conclusion

Synthesis of Findings

The Philippines’ leadership in gender equality stems from a unique blend of pre-colonial egalitarianism, colonial educational reforms, and modern advocacy like the Magna Carta of Women. Women’s prominence in business, government, and family has driven economic growth, inclusive governance, and social cohesion. However, challenges like low labor participation, OFW vulnerabilities, and divorce debates highlight the need for continued progress.

Leveraging Women’s Empowerment for Development and Progress

The Philippines’ model of women’s empowerment offers a powerful blueprint for national development and global inspiration. By further integrating women into the workforce—potentially raising female labor participation from 49% to match men’s 76%—the country could boost GDP by an estimated 7% (World Bank, 2022).

Investing in STEM education for women can drive innovation in tech and green industries, aligning with global sustainability goals. Strengthening protections for female OFWs, such as bilateral labor agreements and mental health support, can maximize their economic contributions while ensuring well-being. In governance, expanding women’s representation through quotas or mentorship programs can enhance policy inclusivity, addressing issues like healthcare and education reform.

Globally, the Philippines can lead by example, exporting its gender equality model through international forums like ASEAN or the UN. By advocating for women’s rights in trade agreements and migration policies, it can influence regional norms. Locally, navigating divorce legalization with sensitivity to cultural values can strengthen women’s autonomy without fracturing social cohesion.

These steps position the Philippines as a hub for gender-driven progress, fostering a society where women’s leadership catalyzes economic, social, and cultural advancement. Other nations can follow suit, recognizing that empowering women is not just a moral imperative but a strategic driver of prosperity.

Crosslinks

- Transforming Philippine Society: A Multidisciplinary Vision for Holistic Renewal — Policy pathways where women’s leadership reshapes education, health, and local governance.

- The Future of Power: From Domination to Stewardship — Reframes leadership models from control to guardianship—how Filipina pioneers keep power in trust.

- Codex of the Living Hubs: From Households to National Nodes — Barangay-level councils, mutual-aid rings, and care infrastructures that multiply women’s impact.

- Redefining Work in a Post-Scarcity World: A New Dawn for Human Purpose and Connection — Centers the care economy; recognizes unpaid labor and designs esteem-based contribution.

- Conscious Capital: Redefining Wealth and Impact — Funding rails and transparent ledgers for women-led enterprises and community funds.

- From Fear to Freedom: Harnessing Consciousness to Transform Media’s Impact — Deprograms stereotypes; replaces exploitative narratives with truth-aligned representation.

9. Glossary

- Babaylan: Pre-colonial Filipino spiritual leaders, often women, with significant community influence.

- Magna Carta of Women: A 2009 Philippine law eliminating discrimination against women in various spheres.

- OFW (Overseas Filipino Worker): Filipinos working abroad, often in feminized roles like nursing or domestic work.

- Gender and Development (GAD) Budget: A mandated 5% allocation in government budgets for gender-focused initiatives.

10. Bibliography

Asia Society. (2022). Women in the Philippines: Inspiring and Empowered. https://asiasociety.org

Grant Thornton. (2020). Women in Business 2020: Putting the Blueprint into Action. https://www.grantthornton.global

Salazar, Z. (2003). The babaylan in Philippine history. In Feminism and the Women’s Movement in the Philippines (pp. 7-8). ResearchGate. https://www.researchgate.net

The Asia Foundation. (2012). Early Feminism in the Philippines. https://asiafoundation.org

World Bank. (2022). Overcoming Barriers to Women’s Work in the Philippines. https://blogs.worldbank.org

Philippine Statistics Authority. (2022). Survey on Overseas Filipinos 2021. https://psa.gov.ph

World Economic Forum. (2021). Global Gender Gap Report 2021. https://www.weforum.org

Attribution

With fidelity to the Oversoul, may this work serve as bridge, remembrance, and seed for the planetary dawn.

Ⓒ 2025–2026 Gerald Alba Daquila

Flameholder of SHEYALOTH · Keeper of the Living Codices

All rights reserved.This material originates within the field of the Living Codex and is stewarded under Oversoul Appointment. It may be shared only in its complete and unaltered form, with all glyphs, seals, and attribution preserved.

This work is offered for personal reflection and sovereign discernment. It does not constitute a required belief system, formal doctrine, or institutional program.

Digital Edition Release: 2026

Lineage Marker: Universal Master Key (UMK) Codex FieldSacred Exchange & Access

Sacred Exchange is Overflow made visible.

In Oversoul stewardship, giving is circulation, not loss. Support for this work sustains the continued writing, preservation, and public availability of the Living Codices.

This material may be accessed through multiple pathways:

• Free online reading within the Living Archive

• Individual digital editions (e.g., Payhip releases)

• Subscription-based stewardship accessPaid editions support long-term custodianship, digital hosting, and future transmissions. Free access remains part of the archive’s mission.

Sacred Exchange offerings may be extended through:

paypal.me/GeraldDaquila694

www.geralddaquila.com - Introduction

-

Thought Experiment: Can the Philippines Become a True Paradise on Earth?

Exploring the Role of Elevated Consciousness in Transforming Society Through a Multi-Disciplinary Lens

Prepared by: Gerald A. Daquila, PhD. Candidate

9–14 minutesABSTRACT

The Philippines, with its breathtaking natural beauty and warm, hospitable people, holds immense potential to be a “paradise on earth.” Yet, challenges like corruption, poverty, and recurring natural disasters highlight a gap between its idyllic promise and current reality. This dissertation explores whether elevating collective consciousness, as suggested by metaphysical and esoteric teachings such as The Law of One and A Course in Miracles, could be the key to unlocking this potential.

By integrating insights from philosophy, psychology, sociology, and spiritual traditions, this study argues that fostering a sense of unity and interconnectedness may address systemic issues like corruption and scarcity more effectively than traditional investments in infrastructure or education alone. While acknowledging the complexity of societal transformation, the analysis suggests that a shift toward unity consciousness, grounded in both spiritual wisdom and practical reforms, could catalyze profound change. The dissertation concludes with an invitation to reflect on the concept of oneness as a cost-free yet transformative idea for the Philippines and beyond.

Table of Contents

- Introduction

- The Vision of a Philippine Paradise

- Thesis Statement and Research Question

- The Philippines’ Potential and Challenges

- Natural Beauty and Cultural Strengths

- Socioeconomic and Environmental Obstacles

- Theoretical Framework: Consciousness and Unity

- Philosophical Foundations: Self and Society

- Metaphysical and Esoteric Perspectives

- Psychological and Sociological Insights

- Case Studies and Evidence

- Historical Context: Filipino Values and Social Structures

- Modern Challenges: Corruption and Scarcity

- Spiritual Practices and Their Impact

- Analysis: Can Elevated Consciousness Transform the Philippines?

- The Role of Unity Consciousness

- Limitations and Practical Considerations

- Conclusion and Invitation to Reflect

- Glossary

- References

Glyph of the Master Builder

To build is to anchor eternity in matter

1. Introduction

The Vision of a Philippine Paradise

The Philippines is often described as a tropical Eden, with its 7,641 islands boasting pristine beaches, lush mountains, and vibrant biodiversity. Its people, known for their warmth and hospitality, welcome millions of visitors annually, earning accolades as some of the friendliest in the world (Grogan, 2015). Yet, beneath this idyllic surface lie challenges: systemic corruption, widespread poverty, and an average of 20 typhoons annually that disrupt lives and livelihoods (Borgen Magazine, 2021). This thought experiment asks: Can the Philippines become a true paradise on earth, and could elevating collective consciousness be the missing ingredient to unlock its potential?

Thesis Statement and Research Question

This dissertation posits that fostering a collective consciousness rooted in unity, as advocated by metaphysical texts like The Law of One and A Course in Miracles, could address systemic issues like corruption and scarcity more effectively than traditional solutions such as infrastructure or education investments. The central research question is: To what extent can a shift in consciousness, grounded in the principle of oneness, transform the Philippines into a societal paradise? Using a multi-disciplinary lens, this study integrates philosophy, psychology, sociology, and esoteric teachings to explore this possibility.

2. The Philippines’ Potential and Challenges

Natural Beauty and Cultural Strengths

The Philippines’ natural splendor is undeniable. From Palawan’s turquoise lagoons to Bohol’s Chocolate Hills, its landscapes are a global draw, contributing significantly to tourism-driven GDP (World Bank, 2023). Culturally, Filipinos are celebrated for their bayanihan spirit—a tradition of communal unity where neighbors collaborate to solve collective problems, such as relocating homes or rebuilding after disasters (Grogan, 2015). This ethos reflects a deep-seated sense of interconnectedness, aligning with metaphysical principles of unity.

Socioeconomic and Environmental Obstacles

Despite its assets, the Philippines faces persistent challenges. Corruption is a pervasive issue, with the nation ranking 115th out of 180 on the Corruption Perceptions Index (Transparency International, 2024). This “social structure of corruption” infiltrates government, business, and civic life, diverting resources from public goods like infrastructure and education (Quimpo, 2007). Poverty affects 18.1% of the population, with rural areas particularly impacted (Philippine Statistics Authority, 2023). Additionally, frequent typhoons exacerbate economic instability, destroying homes and livelihoods. These issues suggest that material solutions alone—such as building roads or schools—may not address root causes.

3. Theoretical Framework: Consciousness and Unity

Philosophical Foundations: Self and Society

Philosophers like Socrates emphasized self-knowledge as the foundation of wisdom, arguing that understanding one’s strengths and weaknesses fosters ethical living (Abadilla, n.d.). Maurice Merleau-Ponty’s phenomenology further suggests that the self emerges from the interplay of body, mind, and environment, with consciousness shaping perception and action (Abadilla, n.d.). In the Filipino context, this implies that societal transformation begins with individual self-awareness, aligning with the idea that collective change stems from personal growth.

Metaphysical and Esoteric Perspectives

Metaphysical texts like The Law of One propose that all beings are interconnected aspects of a singular Source, and societal issues like conflict and scarcity arise from a “distortion” of separation (Elkins et al., 1984). By embracing unity consciousness, individuals transcend ego-driven behaviors, fostering cooperation and compassion. Similarly, A Course in Miracles teaches that fear, greed, and corruption stem from a belief in separation, which can be healed through forgiveness and love (Foundation for Inner Peace, 1975). These teachings suggest that a collective shift toward oneness could dissolve systemic issues without requiring massive material investments.

Psychological and Sociological Insights

Psychologically, Sigmund Freud’s concept of the unconscious highlights how unexamined beliefs drive behavior, including corruption or hoarding (Abadilla, n.d.). Carl Jung’s notion of the collective unconscious suggests shared archetypes, like unity, can shape societal values. Sociologically, Filipino values such as kapwa (shared identity) and loób (inner self) emphasize interconnectedness, offering a cultural foundation for unity consciousness (Reyes, 2015). However, colonial legacies and weak social infrastructure have entrenched corruption and inequality, undermining these values (Acemoglu & Robinson, 2021).

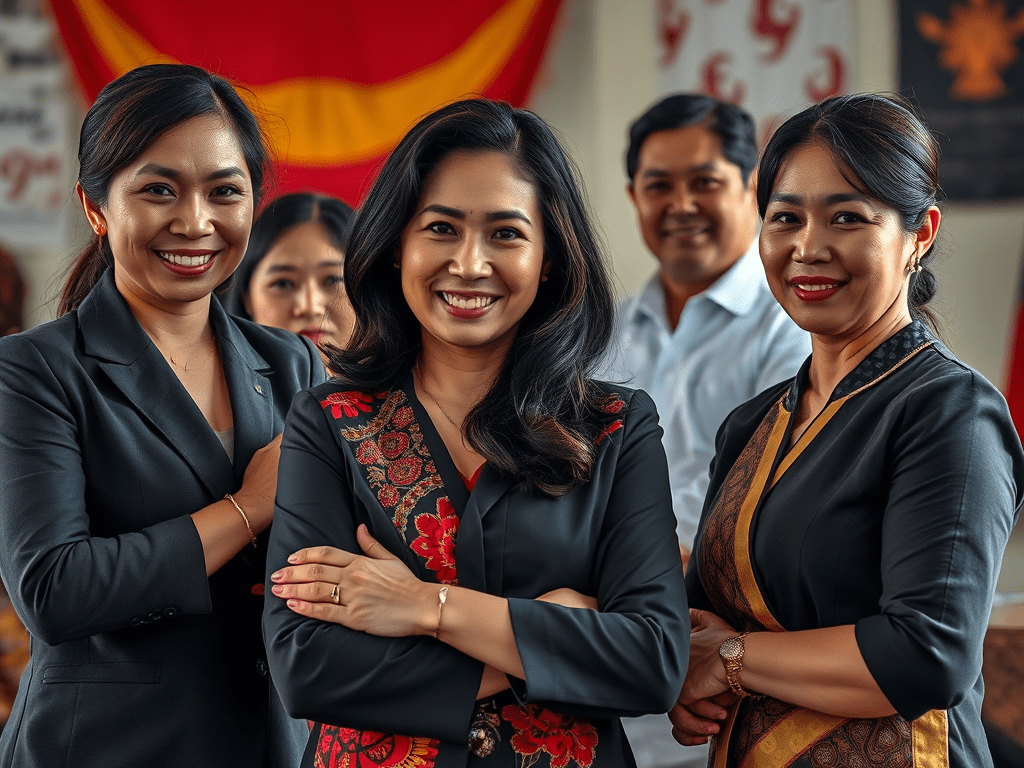

Glyph of the Philippine Paradise

Can the archipelago awaken as true paradise — where sun, land, water, and spirit weave the destiny of a nation reborn?

4. Case Studies and Evidence

Historical Context: Filipino Values and Social Structures

The Philippines’ history reflects both resilience and struggle. Pre-colonial societies thrived on communal values, but Spanish and American colonization introduced hierarchical systems that prioritized elite interests (Constantino, 1975). Despite this, bayanihan and kapwa persisted, evident in community-driven rebuilding efforts post-typhoons. These values align with metaphysical teachings of unity, suggesting a latent cultural readiness for elevated consciousness.

Modern Challenges: Corruption and Scarcity

Corruption in the Philippines is not merely a governmental issue but a social structure woven into patronage networks (Quimpo, 2007). For example, funds for infrastructure projects are often siphoned off, resulting in substandard roads and services (Araneta, 2021). Scarcity, both material and perceived, fuels hoarding and competition, perpetuating a cycle of distrust. Metaphysical texts argue that such behaviors stem from a scarcity mindset, which unity consciousness could reframe as abundance through shared purpose (Elkins et al., 1984).

Spiritual Practices and Their Impact

Small-scale initiatives in the Philippines demonstrate the transformative power of consciousness. For instance, Gawad Kalinga, a community-building movement, leverages bayanihan to construct homes and foster self-reliance, emphasizing collective empowerment (Gawad Kalinga, 2023). Similarly, meditation and mindfulness programs in schools have reduced stress and improved social cohesion, suggesting that spiritual practices can enhance unity (Licauco, 2011). These align with A Course in Miracles’ emphasis on inner peace as a catalyst for societal harmony.

5. Analysis: Can Elevated Consciousness Transform the Philippines?

The Role of Unity Consciousness

The thesis that elevating consciousness can transform the Philippines rests on the principle of oneness. The Law of One suggests that recognizing all beings as part of the Source eliminates fear and greed, dissolving corruption and scarcity (Elkins et al., 1984). In practice, this could manifest as increased transparency, as individuals prioritize collective well-being over personal gain. For example, if public officials internalize kapwa, they may be less likely to embezzle funds, knowing their actions harm the collective self.

Moreover, unity consciousness could shift societal perceptions of scarcity. By fostering trust and cooperation, communities might pool resources, as seen in bayanihan traditions, reducing the need for external investments. Psychological studies support this, showing that mindfulness practices enhance empathy and reduce competitive behaviors (Kabat-Zinn, 2013). In the Philippines, where cultural values already emphasize interconnectedness, this shift seems feasible.

Limitations and Practical Considerations

However, elevating consciousness faces challenges. Deeply entrenched patronage systems and economic inequality create resistance to change (Quimpo, 2007). Metaphysical teachings, while inspiring, lack empirical data on large-scale societal impact, and their abstract nature may alienate pragmatic stakeholders. Education and infrastructure, while not sufficient alone, remain critical for creating conditions where consciousness can flourish—e.g., literacy enables access to spiritual texts, and stable systems reduce survival-driven corruption.

A balanced approach might integrate consciousness-raising with practical reforms. For instance, blockchain-based public registries could enhance transparency while spiritual education fosters ethical behavior (Araneta, 2021). Pilot programs in communities like Gawad Kalinga show that combining material support with values-driven initiatives yields sustainable outcomes.

6. Conclusion and Invitation to Reflect

The Philippines’ natural beauty and cultural strengths position it as a potential paradise, but systemic issues like corruption and scarcity require innovative solutions. This dissertation argues that elevating collective consciousness, rooted in the principle of oneness from metaphysical texts, could address these challenges by fostering unity, empathy, and abundance. While not a panacea, this approach complements material reforms, leveraging Filipino values like kapwa and bayanihan.

An Invitation to the Reader

You have nothing to lose and everything to gain by reflecting on a simple yet profound idea: We are one, all aspects or fractals of the Source.

Pause for a moment. Consider what it means to see every Filipino—every person—as an extension of yourself. How might this shift your actions, your community, our nation? The cost is nothing but a thought, yet the potential is a paradise realized.

Share this thought with your friends and family: Imagine the Philippines, a true paradise on Earth—and it costs not a single peso or centavo. What a gift to our children and to their children, and to the rest of the world!

Crosslinks

- Transforming Philippine Society: A Multidisciplinary Vision for Holistic Renewal – Connects directly to the paradise vision, grounding the thought experiment in real systemic transformation pathways.

- QFS: A New Earth Currency – Illustrates how financial sovereignty and resonance-based exchange are cornerstones for building a Philippine paradise aligned with GESARA.

- Codex of the Living Hubs: From Households to National Nodes – Shows how paradise is built node by node, starting from households and scaling into national stewardship networks.

- A Unified New Earth: A Thesis for Co-Creating Heaven on Earth through THOTH, Law of One, and Quantum Technology – Offers a global context for the paradise experiment, situating the Philippines within a wider planetary co-creation movement.

- From Earth Roles to Soul Roles: A Journey Through the Akashic Fields – Reframes paradise not as utopia, but as souls living authentically in their higher roles, creating collective harmony.

7. Glossary

- Bayanihan: A Filipino tradition of communal unity, often involving collective efforts to solve community problems.

- Kapwa: A Filipino value emphasizing shared identity and interconnectedness with others.

- Loób: The inner self or moral core in Filipino philosophy, guiding ethical behavior.

- Unity Consciousness: A metaphysical concept where all beings are seen as interconnected aspects of a singular Source, reducing separation and conflict.

- The Law of One: A channeled text teaching that all beings are one, and societal issues stem from distortions of separation (Elkins et al., 1984).

- A Course in Miracles: A spiritual text emphasizing forgiveness and love to overcome fear and separation (Foundation for Inner Peace, 1975).

8. References

Abadilla, F. C. (n.d.). Understanding the self: Instructional material. Studocu. https://www.studocu.com

Acemoglu, D., & Robinson, J. A. (2021). Why nations fail: The origins of power, prosperity, and poverty. Crown Business.

Araneta, B. (2021). Interview on corruption in infrastructure projects. The Borgen Project. https://www.borgenmagazine.com

Constantino, R. (1975). The Philippines: A past revisited. Tala Publishing.

Elkins, D., Rueckert, C., & McCarty, J. (1984). The Law of One: Book I. L/L Research.

Foundation for Inner Peace. (1975). A Course in Miracles. Viking Press.

Gawad Kalinga. (2023). Community development programs. https://www.gk1world.com

Grogan, M. (2015). 7 reasons why Filipinos will change the world. Studocu. https://www.studocu.com

Kabat-Zinn, J. (2013). Full catastrophe living: Using the wisdom of your body and mind to face stress, pain, and illness. Bantam.

Licauco, J. (2011). Spirituality is not the same as religiosity. Philippine Daily Inquirer. https://www.inquirer.net

Philippine Statistics Authority. (2023). Poverty statistics. https://psa.gov.ph

Quimpo, N. G. (2007). The Philippines: Political parties and corruption. Southeast Asian Affairs, 2007, 277-294.

Reyes, J. (2015). Loób and kapwa: An introduction to Filipino virtue ethics. Asian Philosophy, 25(2), 148-171.

Transparency International. (2024). Corruption Perceptions Index. https://www.transparency.org

World Bank. (2023). Philippines economic overview. https://www.worldbank.org

Attribution

With fidelity to the Oversoul, may this work serve as bridge, remembrance, and seed for the planetary dawn.

Ⓒ 2025–2026 Gerald Alba Daquila

Flameholder of SHEYALOTH · Keeper of the Living Codices

All rights reserved.This material originates within the field of the Living Codex and is stewarded under Oversoul Appointment. It may be shared only in its complete and unaltered form, with all glyphs, seals, and attribution preserved.

This work is offered for personal reflection and sovereign discernment. It does not constitute a required belief system, formal doctrine, or institutional program.

Digital Edition Release: 2026

Lineage Marker: Universal Master Key (UMK) Codex FieldSacred Exchange & Access

Sacred Exchange is Overflow made visible.

In Oversoul stewardship, giving is circulation, not loss. Support for this work sustains the continued writing, preservation, and public availability of the Living Codices.

This material may be accessed through multiple pathways:

• Free online reading within the Living Archive

• Individual digital editions (e.g., Payhip releases)

• Subscription-based stewardship accessPaid editions support long-term custodianship, digital hosting, and future transmissions. Free access remains part of the archive’s mission.

Sacred Exchange offerings may be extended through:

paypal.me/GeraldDaquila694

www.geralddaquila.com - Introduction