Periods of deep change often surface reactions that feel unfamiliar or uncomfortable: defensiveness, urgency, certainty, comparison, withdrawal, or self-doubt. These responses are frequently described—especially in spiritual or developmental language—as “ego reactions.”

That label is often used loosely, and not always helpfully.

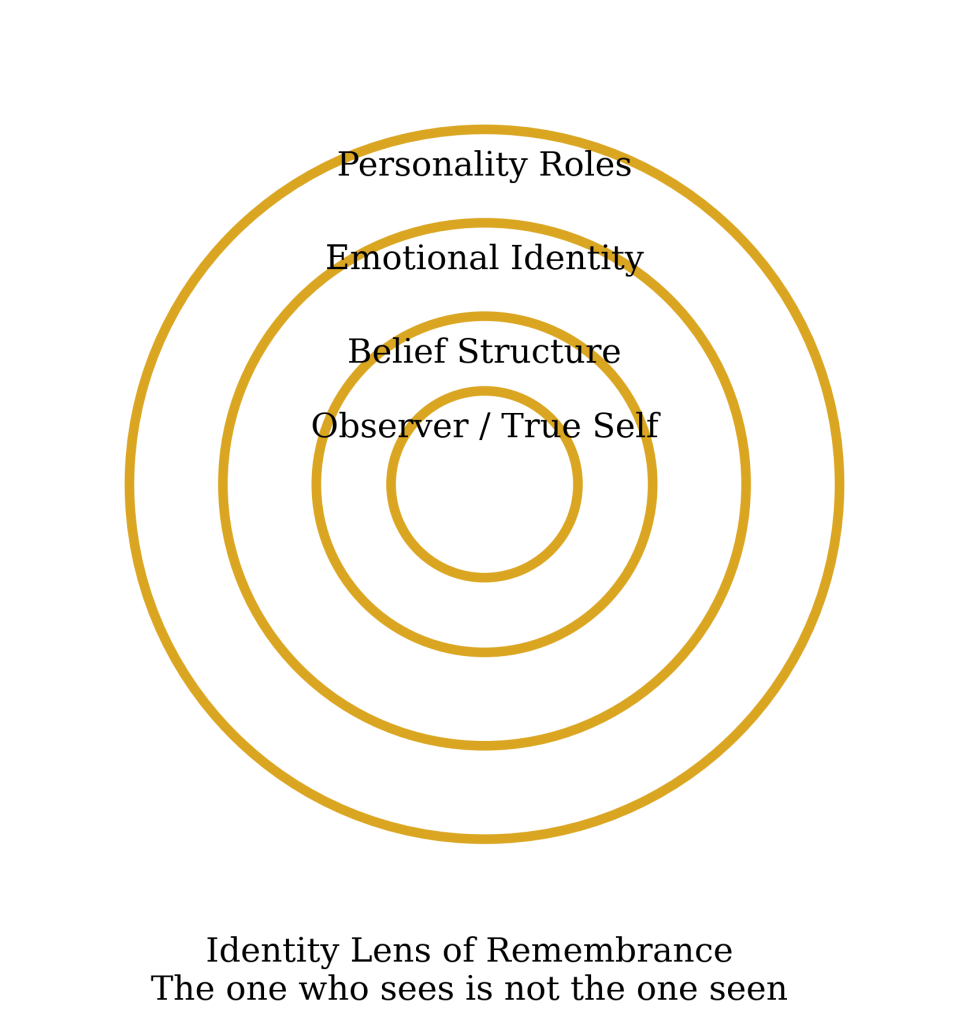

What tends to be missed is that what we call ego is not an enemy to be defeated, nor a flaw to be corrected. It is better understood as a set of identity-maintenance functions that become more visible when stability is threatened.

During transition, the ego is not misbehaving.

It is doing its job—sometimes too loudly.

Ego as a Coherence-Maintenance Function

From a psychological and neuroscientific perspective, human identity is not a fixed object. It is a continuously updated model that helps a person maintain a sense of continuity over time: I am the same person today that I was yesterday, even as things change.

This continuity supports:

- decision-making

- boundary formation

- moral responsibility

- social participation

What is commonly called ego maps closely to these stabilizing functions. It helps organize experience into a story that can be acted upon.

Under ordinary conditions, these functions operate quietly. Under stress—especially during loss, uncertainty, or rapid change—they become more pronounced.

Not because something has gone wrong, but because the system detects risk to coherence.

Why Ego Reactivity Increases During Change

When familiar reference points dissolve, the nervous system registers threat before the mind interprets meaning. Identity, beliefs, and roles are among those reference points.

Neuroscience shows that perceived threats to identity activate many of the same circuits as physical threats. The system prioritizes speed, clarity, and control. Ambiguity becomes uncomfortable. Open-endedness feels unsafe.

In this state, ego responses often intensify:

- certainty hardens

- positions polarize

- comparison increases

- urgency to conclude or convince emerges

These reactions are frequently misinterpreted as arrogance, immaturity, or lack of awareness. More accurately, they are protective accelerations—attempts to restore coherence quickly.

Understanding this removes unnecessary shame.

As described in the companion essay on change and the nervous system, prolonged uncertainty alters perception and narrows capacity. Ego reactivity often intensifies under these same conditions, not as a flaw, but as a stabilizing response.

Two Common Ways Ego Responses Go Off Course

During sensitive transitions, ego activity tends to drift toward one of two extremes. Both are understandable. Both interfere with integration.

1. Ego Inflation

Here, coherence is restored through tightening:

- conclusions arrive quickly

- nuance collapses

- disagreement feels threatening

- certainty substitutes for stability

This often looks like confidence or clarity, but it is brittle. The underlying function is protection, not insight.

2. Ego Erasure

Here, coherence is abandoned rather than tightened:

- self-doubt dominates

- boundaries soften excessively

- voice and preference recede

- responsibility is deferred outward

This is sometimes framed as humility or transcendence, but it often reflects a loss of internal anchoring.

Importantly, both modes are stress responses, not developmental failures.

Why Fighting the Ego Backfires

Because ego activity is tied to safety and continuity, attempts to suppress, eliminate, or “transcend” it during periods of instability often increase internal conflict.

The system interprets ego-attack as additional threat.

This can lead to:

- internal splitting (“part of me is wrong”)

- oscillation between certainty and collapse

- reliance on external authority for direction

- chronic self-monitoring or self-correction

None of these support integration.

The ego does not need to be destroyed.

It needs reduced urgency.

As discussed in the companion essay on change and the nervous system, ego urgency tends to rise as capacity narrows. When that urgency exhausts itself without restoring stability, some people experience moments of acute alarm or panic, which are addressed separately.

What Actually Softens Ego Reactivity

From both psychology and neuroscience, a consistent pattern emerges:

Ego activity decreases as felt safety increases.

Not safety as an idea, but as a physiological condition. When the nervous system stabilizes, identity no longer has to work as hard to defend itself. Perspective widens naturally. Complexity becomes tolerable again.

This shift cannot be forced through insight or effort. It happens through sequencing. Regulation precedes integration.

Several sense-making frameworks map this progression not as moral advancement, but as expanding capacity. Under stress, regression is normal. Under stability, differentiation returns.

Relating to Ego Without Collapsing Into Fear or Self-Erasure

The most stable relationship to ego activity during change is neither indulgence nor suppression, but non-fusion.

This involves recognizing:

- ego responses are signals, not commands

- they intensify when capacity is low

- they soften when conditions stabilize

Observation creates distance without rejection. Distance reduces urgency. Urgency reduction restores choice.

No techniques are required. No practices need to be imposed. The system recalibrates when it is no longer under internal attack.

A Quiet Reframe

If ego reactions are showing up strongly during change, it does not mean you are regressing, failing, or “not ready.”

It means something important is reorganizing.

The presence of ego does not block integration.

The fear of ego often does.

When safety returns, identity loosens without disappearing. Voice remains without hardening. Meaning arrives without force.

That is not ego’s defeat.

It is ego returning to its proper scale.

About the author

Gerry explores themes of change, emotional awareness, and inner coherence through reflective writing. His work is shaped by lived experience during times of transition and is offered as an invitation to pause, notice, and reflect.

If you’re curious about the broader personal and spiritual context behind these reflections, you can read a longer note here.