A Multidisciplinary Exploration of Its Triggers, Types, and Transformative Power

Prepared by: Gerald A. Daquila, PhD. Candidate

ABSTRACT

Cognitive dissonance, a psychological phenomenon introduced by Leon Festinger in 1957, describes the discomfort arising from holding conflicting beliefs, attitudes, or behaviors. This dissertation explores cognitive dissonance through a multidisciplinary lens, examining its triggers, types, and its dual role as a catalyst for personal and societal growth and a potential barrier to progress.

Drawing from psychology, sociology, neuroscience, and philosophy, it investigates how dissonance shapes decision-making, fosters change, and sometimes entrenches resistance. The paper also addresses strategies for overcoming dissonance and its implications for individual self-awareness and societal evolution. By blending academic rigor with accessible storytelling, this work aims to illuminate the profound impact of cognitive dissonance on human behavior and collective dynamics.

Table of Contents

- Introduction: The Uneasy Feeling of Being at Odds with Ourselves

- What Is Cognitive Dissonance?

- Triggers of Cognitive Dissonance

- Types of Cognitive Dissonance

- The Role of Cognitive Dissonance in Growth

- Overcoming Cognitive Dissonance

- A Multidisciplinary Lens: Cognitive Dissonance in Individuals and Society

- The Double-Edged Sword: How Cognitive Dissonance Sets Us Back

- Conclusion: Embracing the Tension for a Better Future

- Glossary

- Bibliography

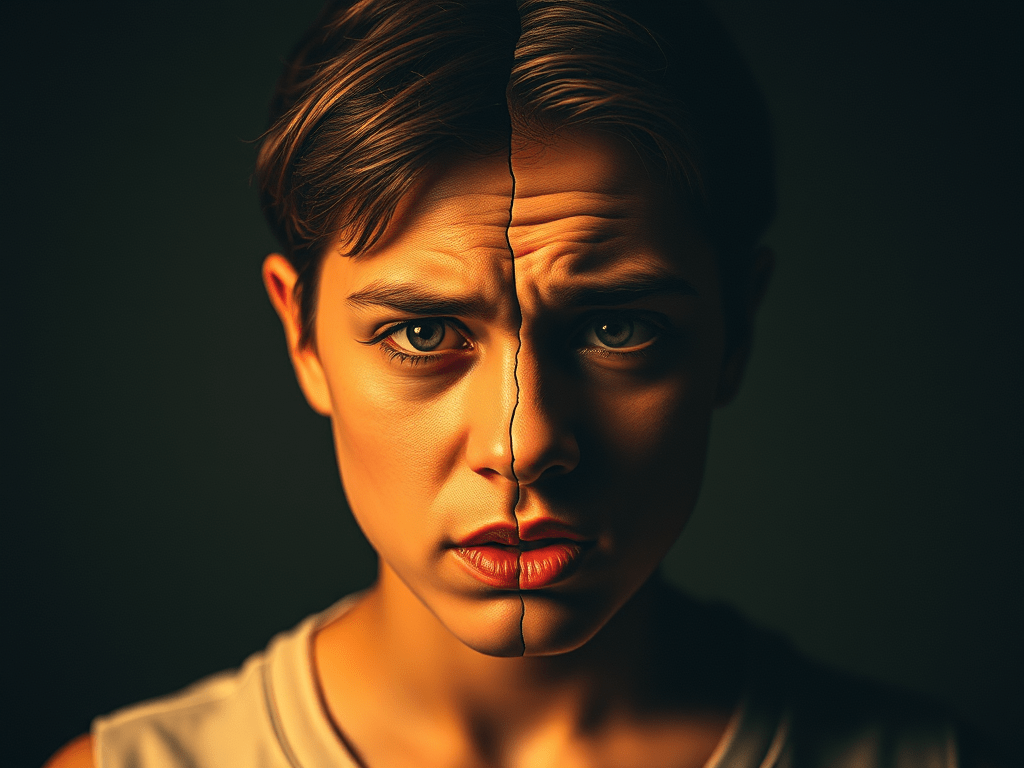

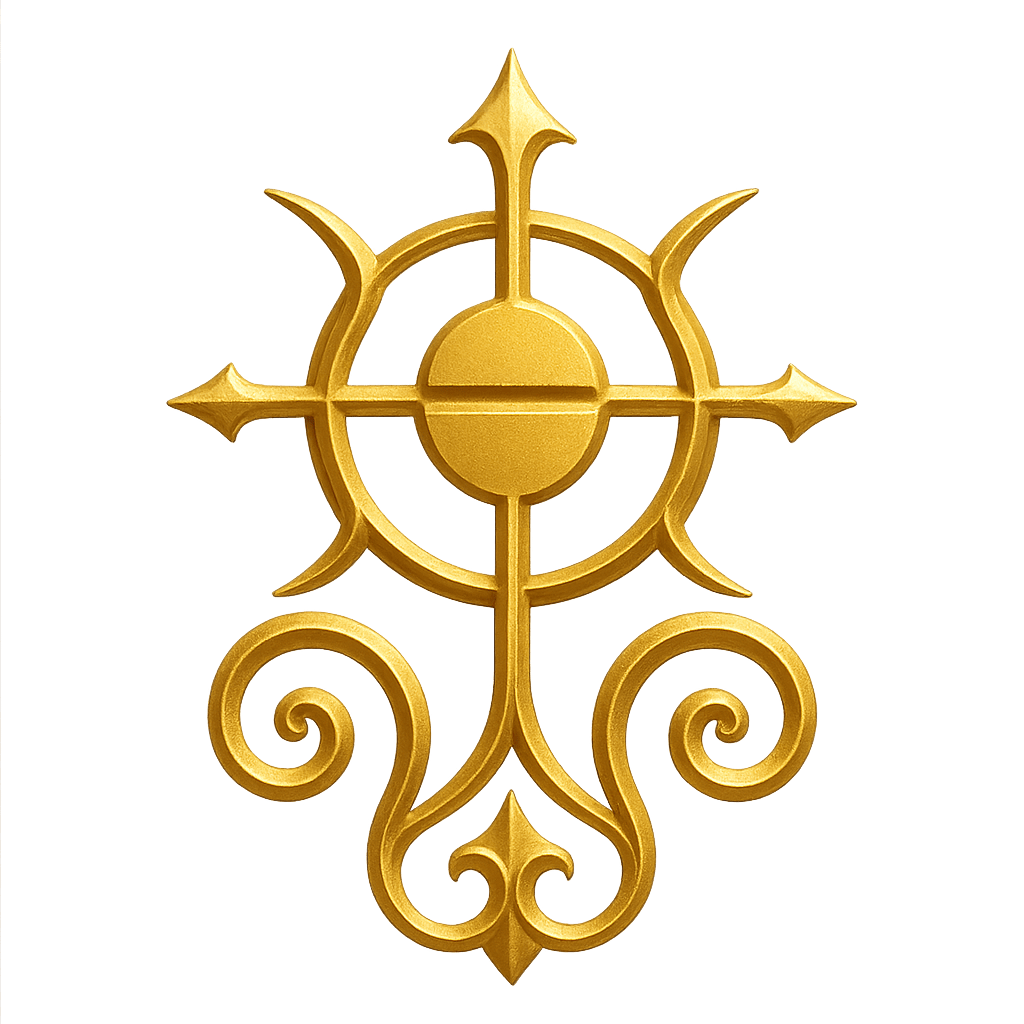

Glyph of the Bridgewalker

Seeing Clearly / Bias & Belief Audit

1. Introduction: The Uneasy Feeling of Being at Odds with Ourselves

Imagine you’re an environmentalist who passionately advocates for sustainability but catches yourself tossing a plastic bottle into the trash instead of the recycling bin. That pang of guilt, that nagging discomfort—it’s not just a fleeting emotion. It’s cognitive dissonance, a psychological tug-of-war that happens when your actions clash with your beliefs. First described by Leon Festinger in 1957, cognitive dissonance is a cornerstone of social psychology, offering insights into why we feel uneasy and how we navigate the contradictions in our minds.

This dissertation dives deep into cognitive dissonance, exploring its triggers, types, and transformative potential. It’s not just about personal discomfort—it’s about how this tension shapes who we are as individuals and how we function as a society. From psychology to neuroscience, sociology to philosophy, we’ll examine how dissonance drives growth, fosters resistance, and challenges us to align our actions with our values. With a narrative that balances logic, emotion, and accessibility, this exploration aims to make a complex concept relatable while maintaining scholarly depth.

2. What Is Cognitive Dissonance?

Cognitive dissonance is the mental discomfort we experience when our beliefs, attitudes, or behaviors are in conflict. Festinger’s seminal work, A Theory of Cognitive Dissonance (1957), posits that humans strive for internal consistency, and when our thoughts or actions don’t align, we feel a psychological tension that motivates us to resolve the inconsistency (Festinger, 1957). For example, if you believe smoking is harmful but continue to smoke, the clash between your belief and behavior creates dissonance.

This discomfort isn’t just a feeling—it’s a motivator. Like hunger drives us to eat, dissonance pushes us to restore harmony, either by changing our behavior, altering our beliefs, or justifying the inconsistency. Festinger’s theory was revolutionary because it challenged the behaviorist view that external rewards solely drive behavior, highlighting instead the internal, cognitive processes that shape our actions (Cooper, 2007).

3. Triggers of Cognitive Dissonance

Cognitive dissonance arises in various situations, often tied to our core values, decisions, or social pressures. Here are the primary triggers:

- Behavior-Belief Conflict: When actions contradict beliefs, dissonance emerges. For instance, a person who values health but skips exercise may feel guilty, prompting dissonance (Harmon-Jones & Mills, 2019).

- Forced Compliance: When external pressures force someone to act against their beliefs, dissonance follows. Festinger and Carlsmith’s (1959) classic experiment showed that participants paid $1 to lie about a boring task experienced more dissonance than those paid $20, as the small reward didn’t justify the lie, leading them to rationalize their behavior by convincing themselves the task was enjoyable (Festinger & Carlsmith, 1959).

- Decision-Making: Choices, especially between two appealing options, create dissonance because selecting one means forgoing the other. This “post-decision dissonance” leads people to emphasize the chosen option’s benefits and downplay the rejected one’s value (Knox & Inkster, 1968).

- New Information: Encountering information that challenges existing beliefs can trigger dissonance. An environmentalist learning that their favorite coffee brand pollutes rivers may feel uneasy, prompting them to dismiss the information or change their habits (The Decision Lab, n.d.).

- Social Influence: Group dynamics can amplify dissonance. If a person’s beliefs clash with their social group’s norms, they may feel pressure to conform, creating internal conflict (Aronson & Tavris, 2020).

These triggers highlight how dissonance is woven into everyday life, from personal choices to societal pressures.

4. Types of Cognitive Dissonance

While cognitive dissonance is a singular concept, it manifests in different forms depending on the context. Researchers have identified several types, each with unique implications:

- Belief-Behavior Dissonance: The most common type, occurring when actions contradict beliefs. For example, a vegetarian who eats meat at a social event experiences this dissonance (Harmon-Jones & Mills, 2019).

- Post-Decision Dissonance: After making a choice, individuals often feel discomfort about the unchosen option’s benefits. This leads to “spreading apart the alternatives,” where the chosen option is rated more favorably (Brehm, 1956).

- Effort-Justification Dissonance: When significant effort is invested in a task with little reward, individuals justify the effort by valuing the outcome more. For instance, someone who endures a grueling initiation to join a group may value the group more to justify the effort (Aronson & Mills, 1959).

- Induced Compliance Dissonance: When external forces compel someone to act against their beliefs, dissonance arises. This is often seen in workplace settings where employees comply with policies they disagree with (Harmon-Jones, 1999).

Each type underscores the versatility of cognitive dissonance, showing how it operates across personal, social, and professional contexts.

Glyph of Dissonant Harmony

Within the tension of opposing truths, the mind and society discover pathways to growth

5. The Role of Cognitive Dissonance in Growth

Cognitive dissonance is more than discomfort—it’s a catalyst for growth. By forcing us to confront inconsistencies, it pushes us toward self-awareness and change.

Individual Growth

Dissonance acts as a psychological signal that something’s off, prompting reflection and adaptation. For example, a smoker who acknowledges the health risks may quit to align their behavior with their values, fostering personal growth (Harmon-Jones, 2019). This process aligns with Festinger’s idea that dissonance motivates us to reduce tension, often by aligning actions with core beliefs.

Therapeutic interventions, like the Body Project for eating disorders, leverage dissonance to encourage healthier behaviors. By highlighting inconsistencies between body image beliefs and actions, participants are motivated to adopt positive changes, improving mental health (Stice, Rohde, & Shaw, 2013). Dissonance also enhances decision-making by encouraging critical reflection, leading to more aligned choices over time (Cooper, 2007).

Societal Growth

At a societal level, dissonance can drive collective change. Activists often highlight contradictions between societal values (e.g., equality) and practices (e.g., discrimination) to inspire reform (Simply Put Psych, 2024). For instance, the civil rights movement used dissonance to challenge the gap between America’s ideals of freedom and its racial inequalities, spurring legislative and cultural shifts.

Dissonance also fosters societal learning. When new information, like climate change data, challenges collective beliefs, it can prompt policy changes or grassroots movements, as seen in the rise of environmentalism (Aronson & Tavris, 2020). By exposing inconsistencies, dissonance encourages societies to evolve toward greater coherence and justice.

6. Overcoming Cognitive Dissonance

Resolving cognitive dissonance is a natural human response, but the strategies vary in effectiveness and impact. Here are common approaches:

- Change Behavior: Aligning actions with beliefs is the most direct way to reduce dissonance. A smoker might quit, or an environmentalist might switch to eco-friendly products (Festinger, 1957).

- Change Beliefs: Adjusting beliefs to match behavior is common when changing actions is difficult. A smoker might downplay health risks, convincing themselves the danger is minimal (Harmon-Jones & Mills, 2019).

- Justify the Inconsistency: Rationalization involves adding new cognitions to bridge the gap. For example, someone who lies might justify it as a “white lie” to avoid hurting feelings (Cooper, 2007).

- Seek Consonant Information: People may seek information that supports their behavior or beliefs, a form of confirmation bias. An anti-vaxxer might ignore scientific evidence and focus on anecdotal stories (The Decision Lab, n.d.).

- Avoid Dissonance-Provoking Situations: Avoiding conflicting information or situations can prevent dissonance. For instance, someone might avoid news about climate change to maintain their lifestyle (Aronson & Tavris, 2020).

While these strategies reduce discomfort, not all promote growth. Changing behavior or beliefs thoughtfully fosters alignment, while rationalization or avoidance can entrench harmful patterns. Therapeutic approaches, like cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT), help individuals confront dissonance constructively, promoting lasting change (Positive Psychology, 2021).

7. A Multidisciplinary Lens: Cognitive Dissonance in Individuals and Society

Cognitive dissonance transcends psychology, influencing fields like neuroscience, sociology, and philosophy, each offering unique insights into its role.

Psychological Perspective

Psychologically, dissonance is a drive state, akin to hunger, motivating action to restore harmony (Festinger, 1957). Studies show physiological markers, like increased galvanic skin response and heart rate, during dissonance-inducing tasks, confirming its aversive nature (Croyle & Cooper, 1983). The action-based model suggests dissonance aids decision-making by reducing ambivalence, enabling decisive action (Harmon-Jones, 1999).

Neuroscientific Perspective

Neuroscience reveals that dissonance activates brain regions like the anterior cingulate cortex, associated with conflict detection, and the prefrontal cortex, linked to decision-making (Izuma & Murayama, 2019). These findings suggest dissonance is a biological response to cognitive conflict, driving neural processes that seek resolution.

Sociological Perspective

Sociologically, dissonance shapes group dynamics and social change. Social identity theory suggests that group norms can amplify dissonance when individuals’ beliefs clash with collective values, prompting conformity or rebellion (Tajfel & Turner, 1979). Dissonance also fuels social movements by exposing contradictions, as seen in campaigns against systemic injustices (Aronson & Tavris, 2020).

Philosophical Perspective

Philosophically, dissonance raises questions about truth, morality, and self-deception. It challenges us to confront whether we prioritize comfort over truth, as seen in the just-world fallacy, where people rationalize suffering to maintain belief in a fair world (Lerner, 1980). Philosophers like Sartre also link dissonance to existential crises, where individuals grapple with freedom and responsibility.

Interdisciplinary Synthesis

Together, these perspectives show dissonance as a multifaceted force. It’s a psychological motivator, a neurological signal, a social catalyst, and a philosophical challenge. By pushing individuals and societies to confront inconsistencies, it fosters growth but also reveals our capacity for self-deception.

8. The Double-Edged Sword: How Cognitive Dissonance Sets Us Back

While dissonance can drive growth, it can also hinder progress when resolved maladaptively.

Individual Setbacks

Rationalization and avoidance often perpetuate harmful behaviors. For example, smokers who downplay health risks may delay quitting, harming their health (Harmon-Jones & Mills, 2019). Similarly, confirmation bias—seeking information that aligns with existing beliefs—can entrench flawed perspectives, limiting personal growth (The Decision Lab, n.d.).

Societal Setbacks

At a societal level, dissonance can reinforce polarization. Political polarization, for instance, often stems from dissonance avoidance, where individuals reject evidence that challenges their ideologies (Aronson & Tavris, 2020). This was evident during the COVID-19 pandemic, where some dismissed mask-wearing despite believing in public health, rationalizing their behavior to avoid discomfort (Medical News Today, 2024).

Dissonance can also perpetuate systemic issues. For example, societal mechanisms like meat-animal dissociation—where consumers disconnect meat from its animal origins—reduce dissonance about eating animals, maintaining environmentally harmful practices (Bastian & Loughnan, 2017). Such avoidance stifles collective progress toward sustainability.

Cultural Limitations

Critics note that dissonance theory may not fully account for cultural differences. In collectivist cultures, group harmony often takes precedence, potentially reducing individual dissonance or redirecting it toward social conformity (Simply Put Psych, 2024). This cultural bias limits the theory’s universal applicability and highlights the need for cross-cultural research.

9. Conclusion: Embracing the Tension for a Better Future

Cognitive dissonance is a universal human experience, a tension that both challenges and shapes us. It’s the discomfort of realizing we’re not living up to our values, the unease of tough choices, and the spark that ignites change. By understanding its triggers—behavior-belief conflicts, forced compliance, decisions, new information, and social pressures—we can navigate its types and harness its potential for growth.

For individuals, dissonance is a call to self-awareness, urging us to align our actions with our values. For societies, it’s a catalyst for justice, exposing contradictions that demand reform. Yet, its dark side—rationalization, avoidance, and polarization—reminds us that growth requires courage to confront discomfort rather than evade it.

As we move forward, embracing dissonance means embracing growth. By fostering self-reflection, encouraging open dialogue, and leveraging interdisciplinary insights, we can transform tension into progress, both personally and collectively. Let’s not shy away from the unease but see it as a guide toward a more coherent, authentic future.

Crosslinks

- Connecting the Dots: How the Brain Weaves Stories to Understand the World — Shows how pattern-seeking + bias fabricate “fit,” and how to reality-check narratives.

- The Theater of the Self: Unmasking Identity and the Eternal Soul — Separates persona from essence so you don’t contort truth to protect a role.

- From Fear to Freedom: Harnessing Consciousness to Transform Media’s Impact — Ends algorithmic whiplash; attention hygiene to reduce induced dissonance.

- The Illusion of Separation — Names the root split (me vs. you) that keeps beliefs at war; unity perception softens the clash.

- Understanding Shame: A Multi-Disciplinary Exploration… — Unfreezes identity so you can update beliefs without self-attack or denial.

- Resonance Metrics as a Spiritual Compass in Times of Uncertainty — Somatic dashboard (breath, coherence, relief) for real-time go / hold / repair when beliefs and behavior diverge.

10. Glossary

- Cognitive Dissonance: Psychological discomfort from holding conflicting beliefs, attitudes, or behaviors.

- Cognitive Dissonance State (CDS): The aversive arousal triggered by cognitive inconsistency.

- Consonant Cognitions: Thoughts or behaviors that align logically with each other.

- Post-Decision Dissonance: Discomfort after choosing between alternatives, leading to justification of the chosen option.

- Effort-Justification Dissonance: Valuing an outcome more due to the effort invested in it.

- Induced Compliance Dissonance: Discomfort from being compelled to act against one’s beliefs.

- Confirmation Bias: Seeking information that supports existing beliefs to avoid dissonance.

- Action-Based Model: A theory suggesting dissonance aids decisive action by reducing ambivalence.

11. Bibliography

Aronson, E., & Mills, J. (1959). The effect of severity of initiation on liking for a group. Journal of Abnormal and Social Psychology, 59(2), 177–181. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0041593

Aronson, E., & Tavris, C. (2020, July 14). The role of cognitive dissonance in the pandemic. The Atlantic. https://www.theatlantic.com/ideas/archive/2020/07/role-cognitive-dissonance-pandemic/614074/

Bastian, B., & Loughnan, S. (2017). Resolving the meat-paradox: A motivational account of morally troublesome behavior. Personality and Social Psychology Review, 21(3), 278–297. https://doi.org/10.1177/1088868316647562

Brehm, J. W. (1956). Postdecision changes in the desirability of alternatives. Journal of Abnormal and Social Psychology, 52(3), 384–389. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0041006

Cooper, J. (2007). Cognitive dissonance: 50 years of a classic theory. SAGE Publications.

Croyle, R. T., & Cooper, J. (1983). Dissonance arousal: Physiological evidence. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 45(4), 782–791. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.45.4.782

Festinger, L. (1957). A theory of cognitive dissonance. Stanford University Press.

Festinger, L., & Carlsmith, J. M. (1959). Cognitive consequences of forced compliance. Journal of Abnormal and Social Psychology, 58(2), 203–210. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0041593

Harmon-Jones, E. (1999). Toward an understanding of the motivation underlying dissonance effects: Is the production of aversive consequences necessary? In E. Harmon-Jones & J. Mills (Eds.), Cognitive dissonance: Progress on a pivotal theory in social psychology (pp. 71–99). American Psychological Association.

Harmon-Jones, E., & Mills, J. (2019). An introduction to cognitive dissonance theory and an overview of current perspectives on the theory. American Psychological Association. https://www.apa.org/pubs/books/Cognitive-Dissonance-Intro-Sample.pdf

Izuma, K., & Murayama, K. (2019). Neural basis of cognitive dissonance. In E. Harmon-Jones (Ed.), Cognitive dissonance: Reexamining a pivotal theory in psychology (2nd ed., pp. 227–245). American Psychological Association.

Knox, R. E., & Inkster, J. A. (1968). Postdecision dissonance at post time. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 8(4, Pt.1), 319–323. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0025528

Lerner, M. J. (1980). The belief in a just world: A fundamental delusion. Springer.

Medical News Today. (2024, January 15). Cognitive dissonance: Definition, effects, and examples. https://www.medicalnewstoday.com/articles/326738

Positive Psychology. (2021, February 8). Cognitive dissonance theory: A discrepancy between two cognitions. https://positivepsychology.com/cognitive-dissonance-theory/

Simply Put Psych. (2024, June 19). What is cognitive dissonance? Definition, examples, and applications. https://simplyputpsych.co.uk/what-is-cognitive-dissonance-definition-examples-and-applications/

Stice, E., Rohde, P., & Shaw, H. (2013). The Body Project: A dissonance-based eating disorder prevention intervention. Oxford University Press.

Tajfel, H., & Turner, J. C. (1979). An integrative theory of intergroup conflict. In W. G. Austin & S. Worchel (Eds.), The social psychology of intergroup relations (pp. 33–47). Brooks/Cole.

The Decision Lab. (n.d.). Cognitive dissonance. https://thedecisionlab.com/biases/cognitive-dissonance

Attribution

With fidelity to the Oversoul, may this work serve as bridge, remembrance, and seed for the planetary dawn.

Ⓒ 2025–2026 Gerald Alba Daquila

Flameholder of SHEYALOTH · Keeper of the Living Codices

All rights reserved.

This material originates within the field of the Living Codex and is stewarded under Oversoul Appointment. It may be shared only in its complete and unaltered form, with all glyphs, seals, and attribution preserved.

This work is offered for personal reflection and sovereign discernment. It does not constitute a required belief system, formal doctrine, or institutional program.

Digital Edition Release: 2026

Lineage Marker: Universal Master Key (UMK) Codex Field

Sacred Exchange & Access

Sacred Exchange is Overflow made visible.

In Oversoul stewardship, giving is circulation, not loss. Support for this work sustains the continued writing, preservation, and public availability of the Living Codices.

This material may be accessed through multiple pathways:

• Free online reading within the Living Archive

• Individual digital editions (e.g., Payhip releases)

• Subscription-based stewardship access

Paid editions support long-term custodianship, digital hosting, and future transmissions. Free access remains part of the archive’s mission.

Sacred Exchange offerings may be extended through:

paypal.me/GeraldDaquila694

www.geralddaquila.com