Preface

There is a particular moment in prolonged change when something subtle shifts.

The chaos hasn’t fully ended.

The losses are still real.

But the sense that everything is merely happening to you begins to loosen.

Not because you’ve “figured it out.”

Not because the system suddenly became fair.

But because you start to notice that how you relate to change matters—sometimes profoundly, sometimes only marginally, but never not at all.

This essay is about that narrow, often misunderstood space between control and helplessness. About what it actually means to be “in the driver’s seat” of change—without lying to yourself, over-promising outcomes, or blaming yourself when things don’t work.

The myth of total agency—and its quieter cousin, total helplessness

Most narratives about change collapse into one of two extremes.

The first insists that if you take enough initiative, think clearly enough, or stay positive enough, you can steer change wherever you want. When this fails—as it often does—it leaves people feeling defective, naïve, or ashamed.

The second swings hard in the opposite direction: systems are too powerful, circumstances too fixed, timing too unforgiving. The only sane response is endurance. Keep your head down. Wait it out.

Both narratives are incomplete.

From lived experience as a change agent—across organizations, identities, and life phases—I’ve seen moments when initiative genuinely mattered, and moments when it backfired spectacularly. I’ve seen carefully planned interventions succeed against the odds, and well-intentioned effort accelerate collapse.

The mistake is assuming that agency is an all-or-nothing condition.

It isn’t.

If you’re still in the phase where change feels like something that happened to you, you may want to read “Disorientation After Forced Change” first, which names the bodily and cognitive fog that often precedes any real sense of agency.

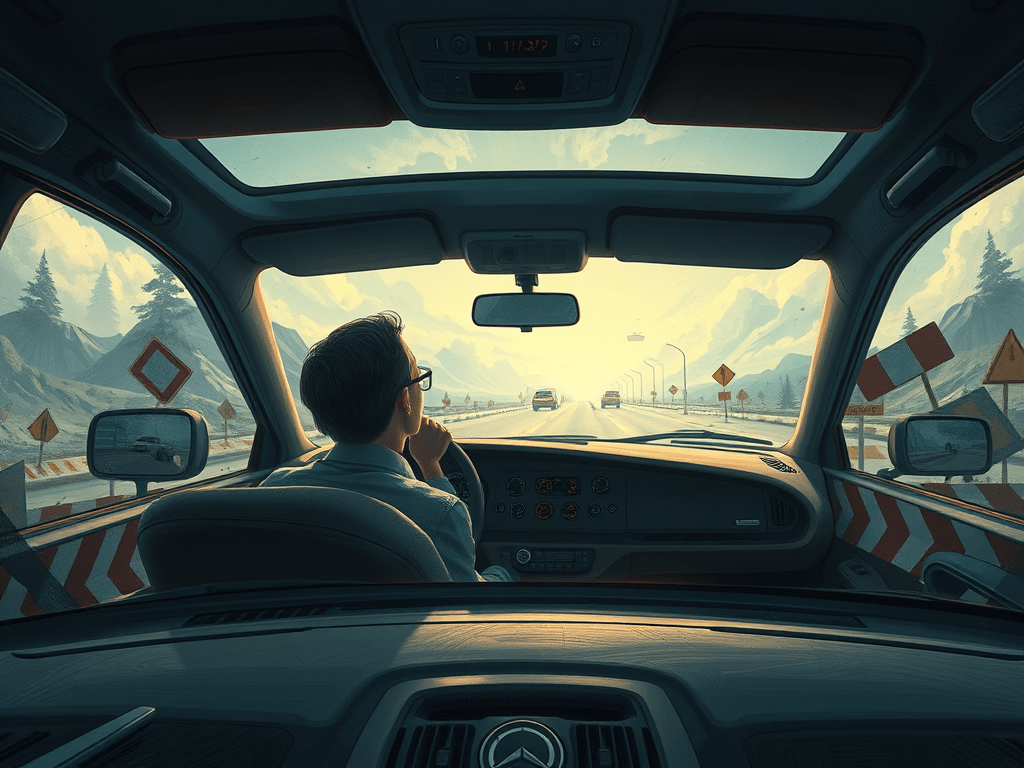

Driver vs passenger is not about control

When people talk about being “in the driver’s seat,” it’s often framed as dominance: steering forcefully, choosing direction, overriding obstacles. In real change contexts, that image does more harm than good.

A more accurate distinction is this:

- Being a passenger means relating to change only after it has already acted on you.

- Being a driver means participating in timing, pacing, and response—even when the destination is uncertain.

You don’t control the weather.

You don’t control traffic.

You don’t control whether the road ahead is damaged.

But you do choose:

- When to accelerate and when to slow down

- When to take a detour and when to stop trying to optimize

- When gripping the wheel harder increases risk rather than safety

This is a humbler form of agency. It doesn’t promise arrival. It increases the odds of remaining intact.

What lived experience teaches that theory doesn’t

Early in my work with change—professional and personal—I believed clarity plus effort would eventually win. When outcomes improved, I credited skill. When they didn’t, I assumed insufficient rigor or resolve.

What years of mixed results taught me instead was this:

- Timing matters more than correctness.

An accurate insight delivered too early or too forcefully can destabilize a system—or a self—beyond repair. - Some resistance is information, not opposition.

Pushing through it blindly often means you’ve mistaken motion for progress. - Survival is sometimes the success metric.

Not every phase of change is meant to produce visible wins. Some are about conserving coherence until conditions shift. - Agency shrinks and expands over time.

Treating it as constant leads either to burnout or to learned helplessness.

These are not inspirational lessons. They are practical ones, often learned the hard way.

Choosing agency without over-promising outcomes

At this in-between state, many people are emerging from experiences where effort did not correlate with reward—job loss, social dislocation, reputational damage, identity collapse. Telling them “you just need to take control” is not empowering. It’s invalidating.

A more honest frame sounds like this:

- You can’t guarantee outcomes.

- You can influence trajectories.

- You can reduce unnecessary harm.

- You can choose responses that preserve future optionality.

Being in the driver’s seat doesn’t mean insisting the car go faster. Sometimes it means pulling over before something breaks.

This connects closely to the earlier essay on disorientation after forced change, where the nervous system is still recalibrating and urgency distorts judgment. It also builds on the relief described in letting go of others’ expectations, where false performance is recognized as a drain rather than a virtue.

Agency that ignores regulation is not agency—it’s compulsion wearing a nicer outfit.

This builds directly on “When Change Settles and You Don’t Feel Better”, which explores why clarity often arrives before the nervous system is ready to act on it.

How agency actually increases survival odds

From experience, agency helps most when it is applied in three specific ways:

1. Naming what is no longer workable

Not fixing it. Not reframing it. Simply acknowledging that a previous strategy, identity, or pace has expired.

This alone can shift internal dynamics from panic to orientation.

2. Choosing smaller, reversible actions

When stakes are high and visibility is low, the most powerful moves are often modest ones that preserve room to adjust.

This is how drivers stay on the road during fog.

3. Withholding action when action would satisfy anxiety rather than reality

Some of the most consequential “driver” moments are refusals—to react, to announce, to escalate.

This is counterintuitive, especially for capable people. But restraint is not passivity when it is chosen deliberately.

You are not late—you are recalibrating

Many readers at this stage secretly believe they are behind. That others figured something out sooner. That their period of being a “passenger” represents failure.

From a change perspective, that interpretation is often wrong.

Periods of apparent passivity are frequently:

- Integration phases

- Sensemaking pauses

- Nervous system repairs after prolonged threat

Trying to force agency prematurely can prolong recovery.

Being in the driver’s seat sometimes begins with admitting you were exhausted—and stopping long enough to feel it.

A quieter definition of agency

If there is a single redefinition this essay offers, it is this:

Agency is not the power to decide outcomes.

It is the capacity to stay responsive without abandoning yourself.

That capacity grows unevenly. It contracts under pressure. It returns in fragments before it stabilizes.

If you find yourself newly able to choose when to engage, when to wait, and when to let something pass without self-blame—you are already more “in the driver’s seat” than you think.

This essay is part of a wider set of lived accounts on surviving change through orientation rather than certainty. If sensemaking through concrete experience is helpful, the earlier pieces form a loose progression rather than a required sequence.

Not in control.

But awake.

And that, in real change, is often the turning point.

About the author

Gerry explores themes of change, emotional awareness, and inner coherence through reflective writing. His work is shaped by lived experience during times of transition and is offered as an invitation to pause, notice, and reflect.

If you’re curious about the broader personal and spiritual context behind these reflections, you can read a longer note here.

What stirred your remembrance? Share your reflection below—we’re weaving the New Earth together, one soul voice at a time.